May 7, 1915.

It is a clear and crisp early summer afternoon. The sea off the coast of Kinsale is calm, almost welcoming. Quite a change from the earlier misty daybreak. The passage must surely be thankful that the dreadful din of the foghorns has now stopped.

The clock marks just after noon on this fine day for sailing as RMS Lusitania, carrying nearly 2,000 souls on board, steams past the south coast of Ireland at about 18 knots. Passengers mill around the ship, perhaps changing into more appropriate attire for lunch, or maybe getting ready to take a relaxing stroll along the upper decks.

Lusitania’s captain, William Thomas Turner, is well aware that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies. Atlantic crossings are perilous at this time, and a ship of Lusitania’s size and profile makes for an unmistakable target on a clear and calm day. Turner knows that the Royal Navy is well able to keep the German Kriegsmarine in check, but he is not fool enough to believe his ship is safe from other predators of the sea.

German submarine activity in the area had been reported less than 48 hours earlier. U-20, captained by Kapitanleutnant Walter Schwieger, has been patrolling around the south coast of Ireland, sinking three ships over the 5-6 May period. Crucially, news of these sinkings had not reached Queenstown (modern day Cobh) by the time Lusitania was due to sail by, and it was assumed that the submarine threat had subsided.

Nevertheless, two general warnings were issued on May 6, and Turner did act responsibly by taking prudent precautions. He orders the closure of watertight doors, posts double-lookouts, and orders a black-out. Just in case.

At around 11am on the morning of May 7, the Admiralty sends a warning to all ships, reporting that German U-boats are indeed active around the southern area of the Irish Channel. This warning directly related to the sinkings of the previous two days. Turner’s concern grows, and orders Lusitania to steer closer to land, as he thinks that German U-boats operate more comfortably in the open sea. He believes his boat would be safer near the coast.

U-20 was running low on supplies by May 7. She was short on fuel and had only three torpedoes left. The boat surfaced in early morning, only to see mist and fog. Poor visibility would prevent any successful attack, while at the same time increase the chances of colliding against an unseen ship or obstacle, so Schwieger ordered to dive and head for home.

But then, at 12.45, U-20 surfaces again. Visibility had now vastly improved, the earlier fog having lifted by now.

The U-boat’s lookouts spot something far in the horizon, and the captain is called to the conning tower. At first, they assume it to be a group of ships, due to the number of masts and funnels spotted, but the truth is soon discovered. The unmistakable shape of a large steamer soon looms across the distance: Lusitania’s fate is sealed.

Schwieger orders U-20 to dive and pursue the target. The man knows this was a large prize, and would not let go of it that easily.

Onboard the liner, people are blissfully unaware of the mortal danger lurking beneath the waves. It is a clear and bright early summer’s day, so it’s hard to think of anything other than a relaxed afternoon onboard the gigantic and luxurious ocean liner. The sun hangs high over the Irish skies while U-20 is running silent at periscope depth, stalking its prey.

Lusitania steams ahead at 18 knots, with land almost in sight. She is due in Liverpool in just under a day. But she would never make it there.

At 14.10pm on this fine and sunny day of May 07, Kapitanleutnant Walter Schwieger orders one single torpedo to be fired at Lusitania’s starboard bow from a distance of about 700 metres. The weapon exits U-20 and speeds to the ocean liner at a depth of three metres. Its bubbly and deadly wake is spotted by an 18-year-old lookout named Leslie Norton. He shouts a desperate warning through a megaphone, but it makes no difference. The torpedo finds its mark and hits Lusitania dead on, striking the ship just under the bridge.

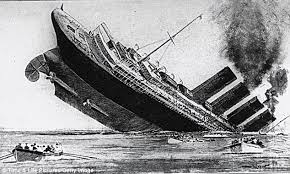

There is an explosion, and almost immediately, a second, larger detonation. Almost at once, Lusitania begins listing to starboard.

At 14.12, Captain Turner orders a hard to starboard turn, towards land, but the ship is mortally wounded. Engine pressure drops rapidly, its steam lifeline bleeding out quickly. Lusitania’s wireless operator issues an SOS, which is acknowledged by a coastal station. The ship’s position is 10 miles south of the Old Head of Kinsale.

Though Lusitania carries 48 lifeboats, more than enough for all passengers and crew, the boat’s heavy listing prevents the launch of most of them. Many overturn while loading or lowering, throwing people helplessly into the sea. Others crash onto lower decks, crushing passengers below. In the end, only six lifeboats are successfully launched, all on the starboard side.

Schwieger watches Lusitania’s death with the cold detachment that only a war enemy can show. At 14.25, he orders U-20 to dive and turn away, heading out to the relatively safety of deeper waters. He would be killed later in the war while commanding U-88. The boat hit a mine while chased by a British destroyer and sank, with no survivors.

Lusitania herself sank in 18 minutes, on May 7, 1915.

Out of its 1,959 passengers and crew, 1,195 were lost in the disaster, many while waiting for help in the cold waters of the Irish Channel. Only 289 bodies were ever recovered, most of which were interred in Queenston and Kinsale.

Turner did live on. He remained in the bridge until water rushed in and washed him overboard. He managed to survive by clinging onto a chair he found floating on the water. He was pulled from the sea unconscious, but alive. By this time, Lusitania’s hulking shape had vanished beneath the waves.

In the aftermath of the disaster, controversy surrounded the event of the liner’s sinking, a controversy which rages to present day. Propaganda, claims, and counterclaims from both sides have somewhat clouded the facts.

The truth remains that the sinking of RMS Lusitania was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, maritime disaster to ever occur on Irish shores.

This week, commemorative events are taking place in and around Cobh and Kinsale, to remember those who perished at sea.